Quick Answer

Understanding worm anatomy helps you become a better worm farmer. Composting worms like red wigglers and European nightcrawlers have fascinating body parts including 5 hearts, no eyes (but light-sensing cells), a specialized digestive system, and over 100 segments. The clitellum (that band you see on mature worms) is their reproductive organ, and setae (tiny bristles) help them move through soil and bedding.

Why Worm Anatomy Matters for Composting

When I started Meme's Worms in 2018, I thought all I needed to know was "feed them scraps, get castings."

I was wrong.

Understanding worm anatomy changed everything about how I manage my bins. Here's why it matters:

The Digestive System determines feeding strategy

Once you understand how the worm digestive system works, you realize why certain foods cause problems. The gizzard needs grit to grind food, the crop stores it temporarily, and the intestine is where nutrients get absorbed and castings are formed.

The Clitellum tells you breeding readiness

That cream-colored band (the clitellum) appears when worms reach sexual maturity. If you want maximum reproduction, you need worms with prominent clitellums—usually 8–12 weeks old for red wigglers.

The skin explains moisture needs

Worms breathe through their skin. This anatomy fact explains why they need 75–85% moisture to survive. Dry skin = dead worms. Now moisture management makes sense.

Setae movement affects bedding choice

Those tiny bristles (setae) help worms grip and move through material. This is why loose, fluffy bedding works better than compacted material—setae need something to grab.

Commercial Insight: In our breeding operation, we select worms based on anatomical features. Prominent clitellums, active movement (strong setae), and plump segments indicate healthy, productive worms. Anatomy literally determines quality.

After 7+ years handling thousands of worms daily, I can identify health issues just by looking at their anatomy. Swollen segments? Protein poisoning. Pale clitellum? Nutritional deficiency. Lethargic movement? Temperature stress affecting their circulatory system.

Let me show you exactly what's inside a worm and how each part affects your composting success.

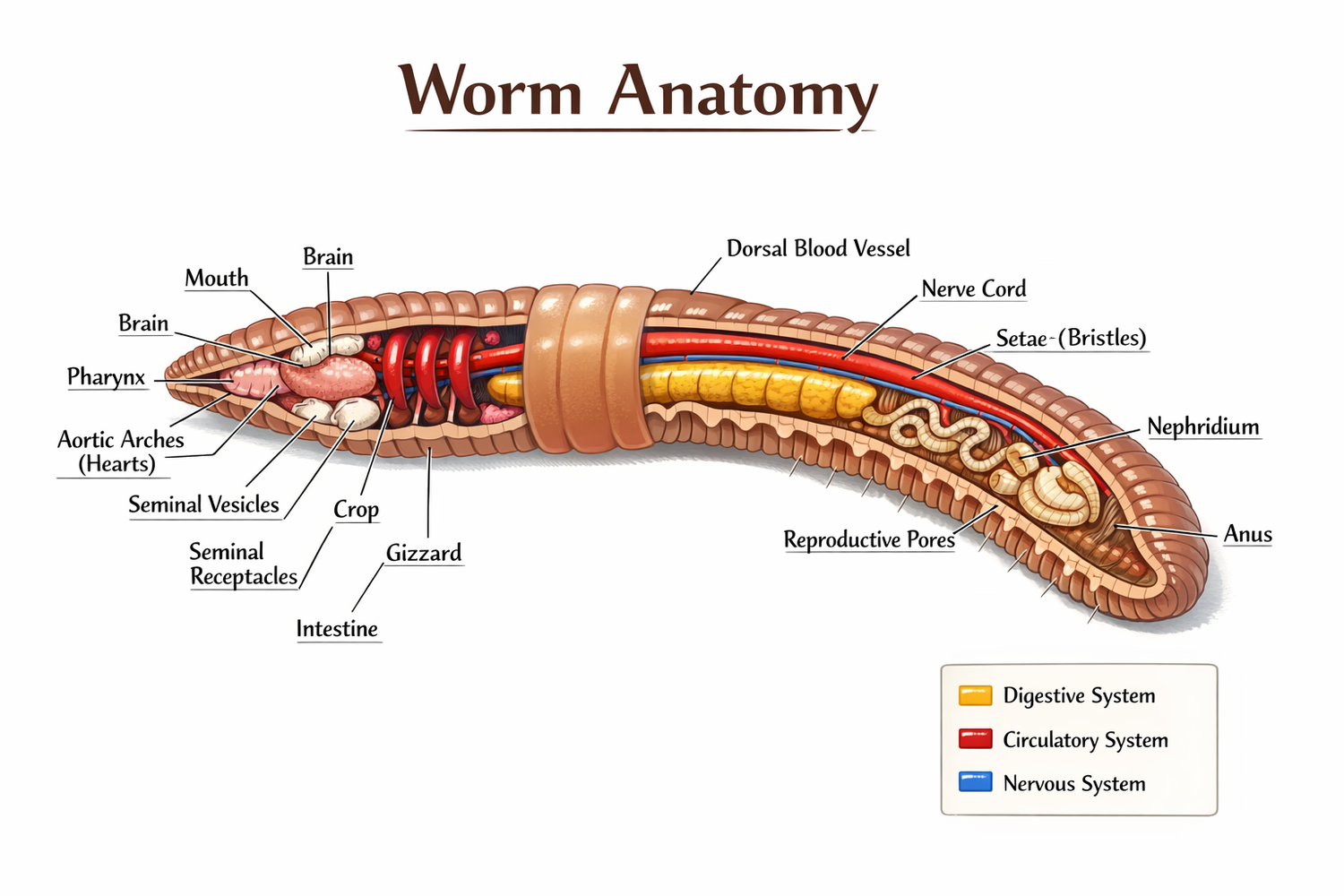

Complete Worm Anatomy Diagram

External Parts (visible without dissection):

- Prostomium (front sensing lobe)

- Segments (100–150 rings)

- Setae (tiny bristles on each segment)

- Clitellum (reproductive band)

- Anus (posterior opening)

Internal Organs (cross-section view):

- Digestive System: Mouth → Pharynx → Esophagus → Crop → Gizzard → Intestine → Anus

- Circulatory System: 5 hearts (aortic arches)

- Excretory: Nephridia (2 per segment)

- Nervous System: Cerebral ganglia ("brain"), ventral nerve cord

- Reproductive: Testes, ovaries, seminal receptacles

Must Read : How to Start a Worm Farm at Home

External Anatomy: Parts You Can See

When you pick up a worm, here's what you're actually looking at:

The Prostomium (Front Sensing Lobe)

What it is: The smooth, fleshy lobe at the very front of the worm

Function of the prostomium:

- Pushes through soil and bedding

- Senses chemicals and moisture

- Covered in chemoreceptors (taste/smell sensors)

- NOT a true head—worms don't have heads

Why it matters:

The prostomium is why worms burrow toward food. They "taste" the bedding ahead and move toward decomposing material. In my bins, I watch worms congregate where I buried food—the prostomium led them there.

Segments (Metameres)

What they are: The ring-like divisions along the worm's body

How many segments do worms have?

- Red wigglers (Eisenia fetida): 95–150 segments

- European nightcrawlers (Eisenia hortensis): 110–170 segments

- Earthworms (Lumbricus terrestris): 110–160 segments

Each segment contains:

- Circular and longitudinal muscles

- Pair of nephridia (kidney-like organs)

- Setae (4 pairs per segment = 8 bristles)

- Section of nerve cord

- Blood vessels

The segments create waves

Worm movement works through segment contraction. Watch a worm move and you'll see waves traveling along the body—that's segments contracting and relaxing in sequence. This movement is called peristalsis (same mechanism in your intestines!).

Segment damage happens

In shipping or handling, segments can get pinched or damaged. Healthy worms usually regenerate minor damage, but severe segment injury can kill them. This is why we pack carefully at Meme's Worms—protecting those segments.

Setae (Bristles)

What are setae on worms?

Setae are tiny, hair-like bristles that protrude from each segment. Think of them as microscopic grappling hooks.

How many setae?

- 4 pairs per segment (8 total)

- On red wigglers: approximately 800–1,200 total setae

- Too small to see individually with naked eye

- Feel rough when you rub worm backward

Setae function:

✓ Grip soil and bedding during movement

✓ Anchor worm during copulation (mating)

✓ Prevent being pulled from burrow by predators

✓ Help navigate through dense material

Why bedding texture matters:

This is the practical application of understanding setae. Loose, fluffy bedding (shredded cardboard, coconut coir) gives setae something to grip. Compacted, dense material makes movement difficult.

In our commercial bins, we keep bedding properly fluffed specifically for setae function. When worms can move easily, they feed more, grow faster, and reproduce better.

Feel for setae: Gently run your finger from tail to head on a worm. Feels smooth. Now go head to tail. Feels rough—that's the setae catching your skin!

The Clitellum (Reproductive Band)

What is a clitellum?

The clitellum is a swollen, glandular band that appears on sexually mature worms. It's the most obvious anatomical difference between juveniles and adults.

Clitellum characteristics:

- Location: Typically 1/3 from head (varies by species)

- Color: Cream, light pink, or orange (lighter than body)

- Texture: Smooth, slightly raised

- Size: 3–8 segments wide

- Appears at: 8–12 weeks for red wigglers, 12–16 weeks for nightcrawlers

The clitellum produces:

- Mucus for mating (binding two worms together)

- Albumen (egg white-like fluid for cocoon)

- Cocoon material that hardens into protective shell

Why the clitellum matters for breeding:

When I select breeding stock, clitellum prominence is #1 criteria. A thick, well-developed clitellum = active reproduction. Pale or barely visible clitellum = low breeding output.

Species clitellum differences:

| Species | Clitellum Segments | Color | Position |

|---|---|---|---|

| Red Wiggler | 26–32 | Cream–orange | Prominent |

| European Nightcrawler | 28–33 | Pink–cream | Very prominent |

| Earthworm | 32–37 | Cream | Subtle |

Internal Anatomy: What's Inside a Worm

Now let's open up a worm (metaphorically) and see what's inside.

Major Organ Systems:

1. Digestive System (Alimentary Canal)

- Runs entire length of body

- One-way flow: mouth to anus

- 7 distinct parts: pharynx, esophagus, crop, gizzard, intestine, typhlosole, anus

2. Circulatory System

- Closed system (blood stays in vessels)

- 5 hearts (aortic arches)

- Dorsal and ventral blood vessels

- Red blood (hemoglobin-based)

3. Nervous System

- Cerebral ganglia ("brain")

- Ventral nerve cord

- Ganglia in each segment

- Sensory cells throughout skin

4. Excretory System

- Nephridia (2 per segment)

- Filter waste from blood

- Excrete through pores

5. Reproductive System

- Testes (male)

- Ovaries (female)

- Seminal receptacles (sperm storage)

- Clitellum (cocoon production)

Let's dive deep into the most important systems.

Must Read : The best worm bin money can buy: Memes Worms Hut

The Worm Digestive System Explained

The worm digestive system is the key to understanding how worms turn trash into black gold (worm castings).

Complete Digestive System Flow:

1. Mouth

- No teeth or jaws

- Muscular pharynx sucks in food

- Saliva moistens material

2. Pharynx

- Muscular pumping organ

- Creates suction to pull food in

- First contact with digestive enzymes

3. Esophagus

- Tube connecting pharynx to crop

- Contains calciferous glands (regulate pH)

- Secretes calcium carbonate

4. Crop (Storage)

- Expandable storage chamber

- Holds food temporarily

- No digestion happens here

- Like a food staging area

The crop explained:

Think of the crop as a waiting room. Food sits here while the gizzard finishes processing the previous meal. This is why overfeeding doesn't speed up casting production—the crop can only hold so much, and the rest goes anaerobic while waiting.

5. Gizzard (Grinding)

- Muscular grinding chamber

- Crushes food into fine particles

- Requires grit (sand, rock dust) to function

- Like a bird's gizzard

The gizzard needs help:

This part of the worm digestive system is why I add crushed eggshells and rock dust to bins. The gizzard uses these hard particles like millstones to grind food. Without grit, the gizzard can't process food effectively.

Earthworm gizzard purpose: Break down large particles into small enough pieces for the intestine to absorb.

Pro Tip: Add 1–2 tablespoons of rock dust or sand per square foot monthly. Your worms' gizzards will work more efficiently, speeding up casting production by 20–30%.

6. Intestine (Absorption & Formation)

- Where nutrients get absorbed

- Where castings form

- Contains typhlosole (increases surface area)

- Longest part of digestive tract

The intestine is where magic happens:

As food moves through the intestine, beneficial bacteria continue breaking it down. The worm absorbs nutrients through the intestinal wall, and what remains becomes castings—perfectly balanced, microbe-rich fertilizer.

Fun fact: The intestine has a fold called the typhlosole that increases surface area by 50%. More surface = more nutrient absorption.

7. Anus

- Posterior opening

- Where castings exit

- One casting per 20–30 minutes when actively feeding

Digestive System Timeline:

- Food intake: 10–20 minutes of feeding per session

- Crop storage: 2–4 hours

- Gizzard grinding: 1–2 hours

- Intestine transit: 6–12 hours

- Total time: 12–18 hours from mouth to casting

This is why you see fresh castings 12–24 hours after feeding!

Species digestive differences:

Red wigglers have slightly faster digestive transit (12–16 hours) compared to European nightcrawlers (16–20 hours). This is one reason red wigglers produce castings faster—more efficient digestive systems.

How Many Hearts Does a Worm Have? (Circulatory System)

This is one of the most common questions I get, and the answer surprises people:

Worms have 5 hearts (technically called aortic arches).

The Worm Circulatory System

Worms have a closed circulatory system, meaning blood stays inside vessels (like humans). But instead of one heart, they have 5 pumping organs arranged around the esophagus.

The 5 Hearts (Aortic Arches):

- Location: Segments 7–11 (near front of worm)

- Function: Pump blood throughout body

- Rhythm: Contract in sequence, creating waves

- Rate: 10–20 beats per minute (varies with temperature)

How the hearts work:

Each of the 5 hearts contracts rhythmically to pump blood. Blood flows:

- Dorsal vessel (top) → carries blood forward toward head

- Through hearts (aortic arches) → pumps blood down

- Ventral vessel (bottom) → carries blood backward toward tail

- Through capillaries in segments → delivers oxygen/nutrients

- Back to dorsal vessel → cycle repeats

Do worms have red blood?

Yes! Worm blood is red because it contains hemoglobin (same oxygen-carrying protein in human blood). You can see this if you accidentally cut a worm—the fluid is red, not clear.

Why 5 hearts instead of 1?

The segmented body design requires distributed pumping. One heart couldn't efficiently pump blood through 100+ segments. Five hearts working together create consistent pressure throughout the body.

Temperature affects heart rate:

Worm hearts beat faster in warm conditions (15–20 bpm at 75°F) and slower in cold (5–10 bpm at 55°F). This is why worms are more active in warm weather—faster circulation = more energy.

Can you feel a worm's hearts beating? Place a worm on your palm and stay very still. With practice, you can feel tiny, rhythmic pulses—that's the hearts working!

What happens if a heart is damaged?

Worms have some redundancy. Losing 1–2 hearts usually isn't fatal if the other 3–4 remain functional. But damage to multiple hearts disrupts circulation and typically kills the worm.

Do Worms Have Eyes? (Sensory Organs)

Short answer: No, worms don't have eyes.

But they CAN sense light.

How Worms See Without Eyes

Instead of eyes, worms have photoreceptor cells scattered throughout their skin, concentrated at both ends (head and tail).

Photoreceptors:

- Detect light intensity (bright vs dark)

- Cannot form images

- Particularly dense on prostomium and tail segments

- Help worms avoid surface (where predators are)

What worms can detect:

✓ Light vs dark

✓ Changes in light intensity

✓ Direction of light source

✓ UV radiation

What worms CANNOT detect:

✗ Shapes or images

✗ Colors

✗ Details or movement

✗ Distance

Why worms avoid light:

Worms are photophobic (light-avoiding). Surface = danger. Sunlight dries skin (remember, they breathe through skin), attracts predators, and increases UV exposure.

This anatomical adaptation is why worms dive deeper when you open a bin. Those photoreceptors sense the light change and trigger escape behavior.

Other Sensory Organs

Worms may lack eyes, but they have other sophisticated sensors:

1. Chemoreceptors (Taste/Smell)

- Concentrated on prostomium

- Detect chemicals in food and soil

- How worms find food in bedding

- Can sense pH, moisture, minerals

2. Touch Receptors

- Throughout entire skin surface

- Detect vibration and pressure

- Help worms avoid predators

- Sense texture of material

3. Moisture Sensors

- Regulate burrowing depth

- Keep worms in optimal moisture zones

- Critical for breathing (skin must stay moist)

How worms navigate:

Without eyes or brain (just ganglia), worms navigate using:

- Chemical gradients (toward food smell)

- Moisture levels (toward wet areas)

- Light avoidance (away from surface)

- Texture sensing (through loose vs compact areas)

Practical application:

Understanding that worms lack eyes but sense light explains bin management. Use dark, covered bins. When harvesting, expose castings to bright light—worms will burrow down, leaving clean castings on top.

How Worms Breathe (Respiratory System)

How do worms breathe?

Worms don't have lungs. They breathe through their skin.

This single fact explains SO MUCH about worm care requirements.

Gas Exchange Through Skin

The breathing process:

- Oxygen dissolves in the moist layer on worm skin

- Oxygen diffuses through skin into blood vessels

- Hemoglobin in blood picks up oxygen

- Blood circulates oxygen to all segments

- Carbon dioxide diffuses out through skin

- Process continues constantly

Why moisture is CRITICAL:

Worm skin must stay moist for gas exchange to work. Dry skin = no oxygen absorption = dead worm.

This anatomical requirement explains:

- Why worms die in dry bedding (can't breathe)

- Why bins need 75–85% moisture (optimal for breathing)

- Why worms surface during rain (saturated soil lacks oxygen)

- Why overwatered bins kill worms (water displaces oxygen)

The moisture balance:

- Too dry → Worms suffocate → Death

- Perfect (80%) → Efficient breathing → Thriving worms

- Too wet → No oxygen in water → Worms flee/die

Oxygen requirements:

Worms need oxygen constantly but use it slowly. They can survive in low-oxygen environments (like deep compost) that would kill most animals. Still, some oxygen is required—completely anaerobic conditions are fatal.

Temperature affects breathing:

Warmer temperatures increase worm metabolism, requiring more oxygen. This is why hot bins (85°F+) are dangerous—worms need more oxygen but also lose moisture faster (making breathing harder).

The Moisture Test: Squeeze a handful of bedding. It should clump together but not drip. This moisture level lets worms breathe efficiently while preventing drowning.

No lungs = no coughing:

Since worms lack lungs, they can't cough or clear irritants. Acidic or toxic materials in bedding directly damage the skin they breathe through. This is why pH management matters—it's literally about lung health.

Species breathing differences:

Red wigglers tolerate slightly drier conditions than European nightcrawlers because their skin is slightly thicker. Nightcrawlers need consistent high moisture to breathe properly.

The Clitellum: Reproduction Central

We touched on the clitellum in external anatomy, but let's dive deeper into this crucial organ.

What is the clitellum (detailed):

The clitellum is a glandular, thickened band of segments that develops when worms reach sexual maturity. It's essentially a cocoon-making factory.

Clitellum structure:

- Made of: Gland cells (mucus-producing)

- Thickness: 2–3x normal segment thickness

- Coverage: 3–8 segments (species dependent)

- Permanence: Stays for life once developed

- Activity: Cyclical (active during breeding season)

The clitellum's 3 jobs:

- Mucus Production (Mating)

During copulation, the clitellum secretes sticky mucus that binds two worms together head-to-tail. This mucus holds them in position for 2–4 hours while they exchange sperm.

- Albumen Production (Nutrition)

The clitellum produces albumen (egg white-like protein) that fills the cocoon. This provides nutrition for developing embryos.

- Cocoon Formation

The clitellum secretes material that forms the cocoon shell. As this tube of material slides off the worm's head, it hardens into the protective cocoon.

Clitellum maturity indicators:

Immature (no clitellum):

- Segments appear uniform

- No color differentiation

- Cannot reproduce

Early maturity (faint clitellum):

- Slight band visible

- Same color as body

- Low breeding activity

Full maturity (prominent clitellum):

- Obvious raised band

- Distinct color (cream/pink/orange)

- Active cocoon production

Peak maturity (thick clitellum):

- Very prominent, swollen band

- Bright coloration

- Maximum breeding output

Why clitellum prominence varies:

- Nutrition: Well-fed worms have bigger clitellums

- Minerals: Calcium-rich diet enhances clitellum development

- Age: Older worms have thicker clitellums (to a point)

- Season: More prominent during optimal breeding temps

- Health: Stressed worms have pale, less-developed clitellums

Selecting Breeding Stock: I only use worms with thick, brightly-colored clitellums for breeding. This single anatomical feature predicts reproductive success better than any other indicator.

Clitellum location by species:

| Species | Clitellum Segments | Distance from Head |

|---|---|---|

| Red Wiggler | 26–32 | About 1/3 |

| European Nightcrawler | 28–33 | About 1/3 |

| Earthworm | 32–37 | Past 1/3 |

→ See the clitellum in action: Complete guide to worm reproduction

Red Wiggler vs European Nightcrawler Anatomy

While both are popular composting worms, their anatomy differs in important ways.

Size & Segment Count

Red Wiggler (Eisenia fetida / andrei):

- Length: 2–4 inches (mature)

- Width: 3–5 mm

- Segments: 95–150

- Weight: 0.5–1.0 grams

European Nightcrawler (Eisenia hortensis):

- Length: 4–6 inches (mature)

- Width: 6–8 mm

- Segments: 110–170

- Weight: 1.0–1.5 grams

Why size matters:

Larger body = more digestive capacity = bigger castings per worm. But red wigglers compensate with higher reproduction rates.

Clitellum Differences

Red Wiggler clitellum:

- Segments: 26–32

- Cream to orange color

- Very prominent when mature

- Appears at 8–12 weeks

Nightcrawler clitellum:

- Segments: 28–33

- Pink to cream color

- EXTREMELY prominent (very thick)

- Appears at 12–16 weeks

The nightcrawler’s clitellum is notably thicker, which correlates with slightly larger cocoons.

Digestive System Comparison

Red Wiggler:

- Faster digestive transit (12–16 hours)

- Smaller gizzard (processes food quickly)

- Higher feeding rate (eats 50–100% body weight daily)

- Prefers partially decomposed material

Nightcrawler:

- Slower digestive transit (16–20 hours)

- Larger gizzard (more grinding capacity)

- Moderate feeding rate (eats 30–50% body weight daily)

- Handles fresher material better

Practical implication:

Red wigglers process scraps faster but need more frequent feeding. Nightcrawlers take longer but produce larger castings per worm.

Circulatory Differences

Both species have 5 hearts, but nightcrawlers have slightly larger aortic arches to pump blood through their longer bodies.

Heart rate comparison (at 70°F):

- Red wiggler: 15–18 beats per minute

- Nightcrawler: 12–15 beats per minute

Larger body = slower heart rate (same principle as elephants vs mice).

Sensory Anatomy

Red Wiggler:

- More photoreceptors (very light-sensitive)

- Strong chemoreceptors (finds food quickly)

- Prefers surface layers of bins

Nightcrawler:

- Fewer photoreceptors (less light-sensitive)

- Strong touch receptors (better burrowing)

- Comfortable at greater depths

Nightcrawlers are more tolerant of occasional light exposure, which makes them slightly easier for beginners to work with.

Skin Anatomy & Breathing

Red Wiggler:

- Thicker skin (slightly more desiccation-resistant)

- Tolerates 70–85% moisture range

- Can survive brief dry periods

Nightcrawler:

- Thinner skin (requires consistent moisture)

- Prefers 80–90% moisture range

- Struggles in fluctuating moisture

This anatomical difference explains why red wigglers are more forgiving for beginners.

Setae Comparison

Both have 4 pairs of setae per segment, but nightcrawler setae are slightly longer (better for deep burrowing through compacted material).

Anatomy & Performance Summary

Choose Red Wigglers if you want:

- Faster processing speed (digestive anatomy)

- Higher reproduction (mature clitellum sooner)

- More forgiving conditions (skin anatomy)

- Surface-feeding behavior

Choose Nightcrawlers if you want:

- Larger individual worms (size anatomy)

- Fishing bait (size matters)

- Cooler temperature tolerance

- Deeper burrowing action

How Anatomy Affects Composting Performance

Understanding worm anatomy isn’t just academic — it directly impacts your bin’s success.

Digestive Anatomy → Feeding Strategy

Crop capacity limits how fast worms can process food. Overfeeding doesn’t speed up production; it causes the crop to overflow, leading to anaerobic conditions.

Best practice based on anatomy:

Feed when ~75% of previous food is gone, giving crops time to empty and gizzards time to grind.

Gizzard Anatomy → Grit Requirements

Gizzards need hard particles to function. Without grit, food passes through partially unprocessed, reducing casting quality.

Best practice:

Add crushed eggshells, rock dust, or sand monthly. Your worms’ gizzards will thank you with better castings.

Skin Anatomy → Moisture Management

Worms breathe through their skin, requiring consistent moisture. But too much water prevents gas exchange.

Best practice:

Maintain ~80% moisture (wrung-out sponge consistency). This supports breathing while preventing drowning.

Clitellum Anatomy → Population Growth

Visible clitellums = breeding-age worms = population growth. Tracking clitellum development tells you when reproduction will accelerate.

Best practice:

Create optimal conditions (≈75°F, 80% moisture, good nutrition) when clitellums start appearing to maximize reproduction.

Heart Anatomy → Temperature Impact

Worm hearts beat faster in warmth, increasing activity. But too much heat stresses the circulatory system.

Best practice:

Keep bins at 65–75°F for optimal heart rate and activity without stress.

Setae Anatomy → Bedding Choice

Setae need something to grip. Compacted bedding makes movement difficult, reducing feeding activity.

Best practice:

Keep bedding loose and fluffy. Fluff weekly to maintain texture that setae can grab.

Segment Anatomy → Damage Prevention

Segments are individually vulnerable. Rough handling can damage multiple segments, killing the worm.

Best practice:

Handle worms gently. In shipping, use plenty of bedding to cushion segments against jostling.

The Anatomy-Based System

At Meme’s Worms, every management decision connects to anatomy:

• Feeding schedule → digestive capacity

• Moisture levels → breathing requirements

• Temperature → heart rate optimization

• Bedding choice → setae function

• Breeding selection → clitellum prominence

Understanding anatomy transformed our operation from guesswork to science.

Ready to See Worm Anatomy in Action?

Now you understand exactly what’s inside a worm and how each part functions — not just what things are called, but why they matter for composting success.

Key Takeaways About Worm Anatomy

✓ 5 hearts pump blood through 100+ segments

✓ No eyes, but powerful light-sensing photoreceptors

✓ Worms breathe through their skin (moisture is critical)

✓ Digestive system turns food into castings in 12–18 hours

✓ Clitellum signals sexual maturity and cocoon production

✓ Setae provide grip for movement and mating

✓ Each species has unique anatomical adaptations that affect performance

Understanding these systems helps you feed better, manage moisture correctly, and grow stronger worm populations.

Leave a comment

All comments are moderated before being published.

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.